If you have ever read much about colonial Cuba and its early literature or have leafed through an illustrated book on Old Havana, you will probably have seen the name “Condesa de Merlin.” Likewise, skimming through accounts of early nineteenth-century Parisian salons and society will reveal the name Comtesse Merlin. Still another name emerges from the genealogical chronicles of the intricately-related old Havana families: María de las Mercedes Santa Cruz y Montalvo. So many names, titles, languages and lands – yet who exactly was she? Until you read the upcoming biography – here is a brief synopsis of Mercedes’ extraordinary life!

Havana

Mercedes Santa Cruz y Montalvo was born in Havana in 1789, the eldest daughter and second child of Joaquín de Santa Cruz y Cárdenas and Teresa Montalvo y O’Farrill, future Counts de San Juan de Jaruco and Santa Cruz de Mopox. Mercedes was born into the heart of the Cuban creole elite, descended on her father’s side from the Santa Cruz, Cárdenas, Calvo de la Puerta and other illustrious Havana names. On her mother’s side, she could claim the wealthy newer names such as Montalvo and O’Farrill, as well as the older Herrera, Chacón, Arriola and Ambulodi families as her own.

Mercedes’ parents left Cuba for Spain shortly after her birth, and she was left in the care of her maternal great-grandmother, Luisa Herrera y Chacón. Settling in Madrid, Joaquin and Teresa became an integral part of the Spanish court of Carlos IV and his Queen, Maria Luisa – close to the royal favorite, Manuel Godoy. Little Mercedes, in the meantime, enjoyed an idyllic childhood with Luisa Herrera, her beloved Mamita, until her father’s return in 1797.

Madrid

In 1802, the thirteen-year-old Mercedes sailed with her father for Spain, to be reunited with her mother and two Spanish-born siblings. Teresa Montalvo hosted one of the most popular tertulias, the Spanish version of a salon with attendees including the aristocracy and the artistic world – men like the poet and playwright Quintana and the painter Goya. Under Teresa’s tutelage, Mercedes received the polish and grooming required for social success – and observed the complex and subtle politics of fashionable society.

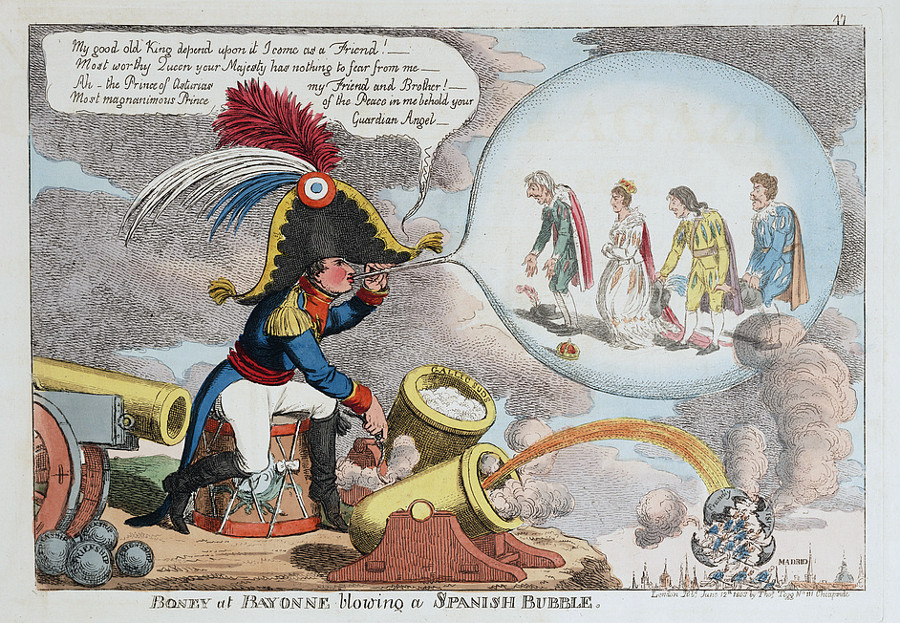

1808 saw the complete upheaval of this world: the Mutiny of Aranjuez overthrew the favorite Godoy and led to the abdication of Carlos IV in favor of his son Fernando VII. Fernando’s rule lasted less than two months as Napoleon, the greatest political force of the era, maneuvered both father and son into abdicating the Spanish crown at Bayonne, across the French border. Mercedes, her two siblings and her widowed mother, under the protection of their uncle General Gonzalo O’Farrill, found themselves under a new regime – one ruled by Napoleon’s elder brother, Joseph Bonaparte. General O’Farrill, initially Fernando’s Minister of War, agreed to serve the new monarch – believing as many did, that no one could defeat Napoleon. But others in Spain disagreed, and the ensuing civil war became known in the English-speaking world as the Peninsular War while the Spaniards called it their War of Independence. Fighting involved the British under Wellington, French forces under Napoleon and later various Marshals, as well as Spanish forces (on both sides) tearing up the entire Peninsula for the next five years.

The five years of war wreaked havoc on Mercedes’ family: their Cuban fortune, already mired in litigation after her father’s death, was cut off due to the fighting, her younger brother Quico was trapped in Paris for the majority of the time, only returning briefly to Spain in 1812 and then escaping to Cuba. Her family’s intimacy with Joseph Bonaparte led Mercedes to a quasi-arranged marriage with a French general almost twenty years her senior, although fortunately for her future happiness – she fell in love with her intended, Christophe-Antoine Merlin. But her mother’s death and the forced evacuation from Madrid in the summer of 1812 – with her two-month-old daughter – meant that she left Spain for French exile without some of her closest family.

Paris

Mercedes lived in Paris for the rest of her life – and what a life it was. Buffeted by the near-constant changes in French political life – Napoleon’s fall in 1814, the first Restorations, Napoleon’s return for the Hundred Days in 1815, the second Restoration, the July 1830 revolution and the installation of Louis-Philippe in the July Monarchy – Mercedes adjusted, adapted and recreated her life and her world. Taking on a starring role in the social milieu, deploying the skills she had learned firsthand from her mother and father, she launched the most celebrated musical salon of the day. Her own angelic voice could be heard partnering some of the greatest professionals of the day, and her musical evenings assured a “passport to celebrity.” Mercedes also used her talents and connections for the public good – establishing a trend for benefit concerts where fashionable society could perform with stars of the musical world. Greek Independence, Polish and Spanish refugees, earthquake victims from Martinique – all benefited from her philanthropy.

Mercedes’s salon also attracted the great of the literary world and the political intelligentsia. She eventually joined the ranks of writers, publishing her memoirs, first focusing on her early Cuban years in 1831 and then eventually covering her life until her arrival in France. Souvenirs and Memoirs de Madame la Comtesse Merlin, Souvenirs d’une Créole, incorporating the first, shorter memoirs, appeared in 1836 and offer a vivid description of a childhood running wild in the Cuban countryside, the world of cloistered Havana convents, a glimpse of the evils of slavery and the fraught years of the Peninsular War. All from the perspective of a woman: daughter, wife and mother.

Havana, Madrid, Paris — encore

Mercedes’ world shifted again after the death of her husband in 1839 and a near-constant struggle to maintain financial stability. After an absence of nearly forty years, Mercedes returned to Havana – looking to establish her future security amidst the remnants of her past. The quintessential exile – never forgetting her beloved homeland, its soft breezes and brilliant colors – returned – as most exiles dream of returning – to acclaim and triumphs. But she also encountered that other aspect of exile: the question of identity and the contradictory role of an exile within their homeland.

Mercedes documented that 1840 voyage to the past in the French-language La Havane and in an abridged Spanish version, Viaje a la Habana. It is the latter which today is most often recalled in Cuba and in Latin American literature – inspiring praise and opprobrium in almost equal measure.

Returning only once more to Cuba in 1849, Mercedes died in 1852, aged 63, in Paris – her beautiful adopted city. She left as many identities as names – as many questions as answers: was she a Cuban-born French writer? Is she a Cuban writer expressing herself in French? Cuba’s first woman author? Did she have the right, as an exile, to comment on her birthplace? Do we call her la Condesa de Merlin or Madame la Comtesse Merlin? Does something remain of Mamita’s spoiled darling – the last link in a family chain? Is she the young woman her Uncle O’Farrill’s called Mercedita?

So, read more about Mercedes, La Belle Créole, to decide who she really was and what you wish to call her. And along the way, rediscover an extraordinary life, a witness to extraordinary times and the long lost worlds of Old Havana, Madrid and Paris.